REBECCA HALL, BEN AFFLECK: THE TOWN

It is an ongoing topic, the virus of sentimentality and how it intersects with narrative in today’s cultural output.

Ben Affleck’s directorial debut of a couple years back was Gone Baby Gone, and it came as something of a shock in the sense that it was so good. Based on the overrated Dennis Lehane novel of the same name, Gone Baby Gone was a hard- edged piece of Boston noir and featured terrific performances from Ed Harris and Amy Ryan. It was pure genre, in the sense that the architecture of plot was never upended and the conventions of such pulp storytelling were closely adhered to. Still, by casting Casey Affleck, an off-kilter sort of actor, and asking him to play against type (a topic to which I will return below) the film had a resonance and the sentimental tropes were forgiven because one felt they were oddly kept (purposely) in the background. It also featured a very taught and smart script.

Affleck’s new film The Town, is also based on a pulp novel and also set in Boston. Why is it so inferior? First, instead of Casey, we have Ben. Affleck as an actor has always seemed a tad slow-witted (which is why he was so funny in Shakespeare in Love) and a bit stilted. But his performance is hardly a problem. The real problem is in the rest of the casting, which reads like a who’s who of industry heat at the moment (Jon Hamm, Blake Lively, Rebecca Hall and Jeremy Renner). These are all “good” actors (well, not Lively) but to somehow stuff them all into what is designed as a modest noir crime film somehow tosses the whole thing out of balance. Lively may be terrible, but she is actually the least culpable of destroying this film. She (or “Gossip Girl”) is simply doing what any agent would suggest to her….stretch and find something a bit more challenging. So, voila, she plays an oxycontin /coke whore hoody chick…and shows cleavage and too much make-up and a decent enough Boston accent. She is bad, but not awful. Still, one wonders if she can really transfer to the big screen. There is something too flat in her eyes, too blank – and she may end up the female Don Johnson of this era. In any event, Hamm is fine….though he isn’t asked to do much. In “Mad Men” his withholding of emotion and that sense of smarts buried beneath the surface is quite compelling and he has a certain grace and a huge dose of masculine gravitas. Here he plays the FBI guy chasing Affleck. Whatever. He is okay.

Renner (who was the ONLY thing I at all liked about Hurt Locker) is rather astonishingly good. He has a wired pent-up edge and a certain vertigo in all his movements that make us want to watch him more each time he appears. He also is one of those actors blessed with preternatural timing. He is a bit like Cagney crossed with Joe Pesci. But then we come to the deal breaker in terms of casting; Rebecca Hall. The RADA brit (now gal pal to Sam Mendes) simply has that snarky look buried behind those big moist eyes. Whenever she and Affleck had a scene I felt like warning too dumb Ben, man, don’t trust this bitch. I don’t know if she can shed that quality, but her prettiness is mixed with an over-ripe squishy quality, and combined with this very mannered acting, the result is unsettling. The performance is “good”; in the sense Meryl Streep is always good. But its not even for a nano second surprising. Her face is always a made face. Her performance is never spontaneous and her sense of “common” is condescending.

The best few moments in the entire film belong to Chris Cooper as Affleck’s bank robber dad, now doing time in Walpole. It’s simply spellbinding.

Throughout the film, I kept thinking of any number of other films that questioned how genre works. No Country for Old Men, Animal Kindgom, or even some of those post Vietnam noirs like Cutter’s Way or Who’ll Stop the Rain. And these reflections on genre led me to think on the way sentimentality creeps into almost all Hollywood studio films.

A film like Animal Kingdom (or A Prophet) could be categorized as genre, but really, they aren’t at all, by virtue of simply up-ending all the conventions. No Country fails because, finally, Cormac McCarthy probably cant be translated to the screen, and what the Coen Bros. end up with is art house genre. Meaning, I think, just a dash too much pretentiousness.

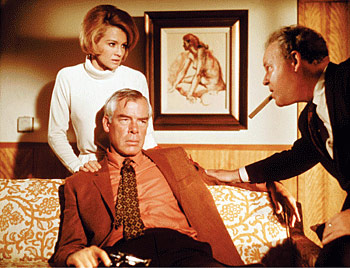

Films such as Bellman and True, the much neglected British bank robbery film, remain pure genre….but of a highly elevated kind. Same could be said for Point Blank, the Boorman classic from the 70s with Lee Marvin. These are both films, that in different ways, work consciously with the conventions of “crime” stories and emerge as almost fable-like achievements. It is worth pondering exactly how this happens. In Point Blank, the surface fetishism of the culture are so finely rendered that one begins to feel that marinated-in quality that often is felt in daily life if stuck in dense traffic on Beverly Blvd or the 605 freeway. Also, Lee Marvin by that point in his career was iconic and allowed himself to move through the proceedings less as an actor than as pure presence. There is a political backdrop to Point Blank (and certainly more overtly in a film like Cutter’s Way) that has to do with the atomized alienation of the populace. In The Town there is, instead, a liberal sort of slumming that creeps into both the script, the performances (some of them) and in the mise en scene. Affleck simply isn’t an intuitive director. He is workmanlike, and it begs the question who the actual auteur of Gone Baby Gone really was.

A Fritz Lang, or a Billy Wilder, are always aware, acutely, of the authority structure. They distrust it and they fear it. Affleck one would suspect never even thinks about such things. In Animal Kingdom, there is never any doubt about the various ways the society exploits and chews up people – on both sides of the criminal fence. The Coen brothers are a bit like Affleck, in the sense that they distance themselves from these realities, and if asked (even by themselves) to render such realities, they do it without resorting to real sweat and blood and tears. It’s that faux classicism that masks a deeply bourgeois mind set.

In Gone Baby Gone, the performance of Casey Affleck offsets such shortcomings. He establishes himself from the start as against not just the other characters, but against the director as well. He is the lightning rod that helps us position ourselves in terms of tweezing apart what matters in this confused moral landscape. This moral complexity, however, is mostly of Casey Affleck’s making, rather than director Ben. In The Town, the moral landscape is absent. It’s not another apologia for the police state, it’s simply that those questions are kept out of the film. And again, part of this is casting. The film turns sentimental not through plot so much as through rendering a reductive universe in which the real history of Boston’s working class neighborhoods is seen as if on display in a Disney Theme park. IF the world that is given us is one dimensional – in social terms at least – sentimentalizing will occur because ANY emotion will be disproportionate.

The universe of Bellman and True or Point Blank is one of pure irrationality, and everyone is a victim of it. There is no room for the sentimental. Same in Winter’s Bone, the narrative is tied so closely to the social reality of the specific region, that even the characters resonate with the shared pain of their collective history.

It is as if in The Town, the ensemble cast is caught up in a rip tide created by the marketing arm of the studio – of maybe of all studios – and only Cooper (and to smaller degree Renner) manage to step away from the undertow and look at the proceedings as we, the audience, do. The role of actor in today’s film is being re-drawn somehow. It may relate to a surveillance society in which everyone is always caught in the gaze of the camera, or perhaps its simply a reality TV conditioned psychology at work, where the effects I describe are as much my fault as the actors. It’s likely that both these forces, and others, are at work in this. This brings us to the notion of “character” in film and theater today. This is a huge topic that would of necessity lead us back to Dante and Shakespeare, if not Sophocles and Homer. Film has always trafficked in various short hands and codes. In films such as The Town, we find ourselves running smack up against the outer walls that contain what is left of the notion of traditional definitions of character. Its not the simplistic short hand of cartoons like The Blind Side (or any other of fifty films in the last three years) but of something more elusive. Jon Hamm’s FBI agent walks through the film as if on loan from his TV show….and so he is. It’s not a cliché role, so much as a non-role. It’s barely a mannequin that we see up there on the screen. It’s only the most fragile of signifiers at work, in context, that gives us any idea about what this “character” is supposed to be doing. These signifiers have been learned through decades, now, of TV (and film). We know when this happens, then this will follow. This is what this “character” must do – for he IS this sort of character.

One wonders if such reactions on the part of an audience translate further into our social selves. I suspect they do. An era of reductive texting passing as communication and of constant recording of “reality” by various kinds of cameras, means just the sheer rapidity of these images and sounds have given us, even if we don’t want them, an endless semi-conscious loop that plays 24 hours a day. We dream in signifiers now, I’m guessing.

In any event, The Town fails horribly to capture any sense of the fatalistic – in the way a Cutter’s Way or Who’ll Stop The Rain (or even a Nightmoves does, or certainly an Out of the Past) manage. That fatalistic dimension, what directors like Lang and Siodmak and Wilder and even Ford used as daily currency for the narrative they spun is now all but impossible to put on the screen. With films like Animal Kingdom we come close, and also in Winter’s Bone, but it’s a diluted version. Those films compensate in other ways; but the pure existential dread of directors like Boetticher or Tourneur or Lang or even Aldrich seems gone.

Watch Point Blank again, and watch Marvin walk purposefully down the empty corridor, and hear those wingtips echo off the floor….. and think if such a scene is any longer possible.

John Steppling

Yucca Valley